HEAT GUN OR IRON FOR VINYL REPAIR?

A Question For The Ages…

By Doug Snow and Kian Amirkhizi

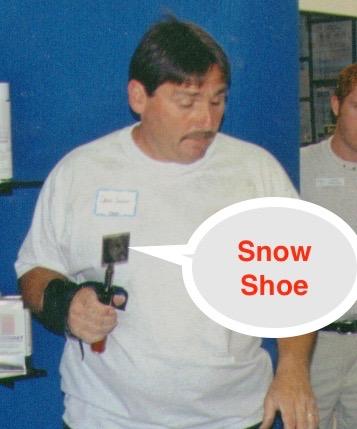

Doug Snow using a heat gun to repair a vinyl restaurant booth.

Recently, on a remote island somewhere in the South Pacific, while finishing my court-ordered enlistment time in the Foreign Legion, I came across an item of such great importance I couldn’t wait to share with our readers. This information came unexpectedly after conducting a secret reconnaissance and rescue mission at a local orphanage.

While I’m sure that many of our readers have been in similar circumstances, something happened that really changed the way I look at things. It had already been a moderately busy day since I had secured the location, liberated captives from the power-mad executive director of the orphanage, survived a terrible bite to the kneecap, and made the prettiest woman on the island swoon as I accepted my hero’s kiss.

As I began to walk back to my hut with the intent of a quiet evening, I heard gunfire erupt as I passed the local library. Despite the fact that no one else around seemed to hear what I did, I did a tuck-and-roll through the nearest doorway and took cover between some dusty bookshelves while pulling my trusty slingshot smoothly from my back pocket.

As I turned to scan the entryway for bogies, I accidentally dislodged a small, tattered leather-bound book, which fell to the ground. When I picked it up, I couldn’t help but notice the title, “Answers to the Questions of the Ages,” written by someone named Doug Snow. The book looked ancient—and since I had heard of Doug Snow and knew he was technically older than Stonehenge—I thought this deserved a closer look.

I flipped open the book and turned to the table of contents. I saw intriguing chapter titles, such as “Achieving Peace in the Middle East,” “Understanding Women,” “How to Open a New DVD Case without Injury,” “What Was that Kid Thinking?” and “Interesting Things to do While Sitting in Traffic.”

Despite this glamorous selection, there was one title that seized my attention. In some ways it was the ultimate question that no one has been able to answer throughout the evolution of human history—or at least in the evolution of vinyl repair.

There in my hands was the answer that all recon technicians seek, “Heat Gun or Iron—Which is the Best for Vinyl Repairs?” Eureka!

Okay, back in the real world now that we have your attention. Despite the fictional imagery of the above story, the “ultimate” question is a true concern for people in our industry. In fact, when we teach vinyl repair, one question that we are seemingly asked every time is “which is the best way to do vinyl repair—with a heat gun or with an iron?”

How We Did It Then

If you ask Doug Snow, he will tell you that the best way to answer this question is to explain how vinyl repair was done back in the horse and buggy days (actually around 1980). Hear him tell it:

“Back then, most people were taught to use a heat gun. The type used was an old cast-iron design made by Master. You would find this type of heat gun at most upholstery shops, and you would purchase it at an upholstery supply house. On the side of the heat gun was an adjustable vent that you would twist, and this would control the air flow which, in turn, controlled the heat. So, the more air you restricted the hotter it would get.

“Generally, it was thought that the hotter you got the repair (without burning it), the better the compound would melt into the substrate. So up until the mid-’80s, this is how most vinyl repairs were done. Some of the repairs would hold up really well, but others would break down or start cracking within a few months. To those of us who were constantly in uncharted areas and trying to discover more about the science of repair, why this happened was a mystery. The repairs looked okay, but were unreliable.

“At that time I worked on auto interiors and furniture (including restaurant furniture and booths). These types of vinyl were completely different from each other. When I was doing repairs on restaurant booths, they would wind up so large that I’d make the grain mold the size of a small pizza and apply it to the back of a serving tray that I would find in the restaurant. I would use that cast-iron heat gun and torch the whole area until it was billowing smoke. Then I would throw down the serving tray with the grain on it to flatten out the repair.

“Sometimes these repairs would hold up. In other times, a month or two down the road they would crack again, and I constantly wondered why. Nowadays, we understand that when you heat up the repair so extremely hot, it leaches the plasticizer (which is what gives the vinyl flexibility) out of the vinyl, making the vinyl dry, brittle and likely to crack.

“I have a confession to make and can only plead inexperience and ignorance. One time, I was doing a dash repair on an old Dodge van. There was a big crack in the speaker grille right in the middle of the dash. The dealer really wanted it repaired, so I decided to attempt it. I filled in the crack with vinyl repair compound and proceeded to heat it up so hot that I had to get out of the car because the smoke fumes were so heavy.

“Bear in mind that our industry was so young then, without all the training, knowledge and resources that are available today. The reason we thought we had to get it so hot was because the crack would billow up like a volcano, and it wouldn’t flatten out until the dash got hot enough to turn the vinyl to liquid. In those days, this was how things were done.

“So following that principle, I got the dash so hot that the foam underneath actually caught on fire! It wasn’t actually in flames, but the foam looked like the end of a cigarette, complete with glowing hot embers.

“Picture this. The speaker grille was in the middle of the dash and directly underneath it was the engine cover. There was no way to get underneath the dash, and an area inside the dash underneath the speaker grille was glowing like a cigarette. I was starting to panic and thinking, ‘oh no, this car is going to completely burn up!’

“I looked around trying to figure out how to put it out. I spotted the soda I was drinking—it was the quickest thing I could get my hands on. I poured the soda through the speaker grille, but it was still smoldering. So I filled the cup with water and poured it in as well. After that, I dried the surface and finished the repair.

“Fortunately, I had a lot of work to do at the dealership. So I kept a wary eye on the van to make sure it didn’t burn up. I’ve always wondered if the water and soda did any damage to the van. The dealership never said anything about it and the van seemed okay. I’m glad that we know better today.

“Another thing I encountered was paper-thin vinyl, such as on Toyota pickup-truck door panels. The vinyl on those door panels was as thin as paper and had no backing for strength. So the first time I put the heat gun to one of those door panels, a quarter-inch hole opened up to the size of a half dollar. I didn’t know what to do or how to fix this problem. So for years I wouldn’t touch those door panels, because they looked terrible after I was done.

“Then something happened that changed everything.”

What We Learned To Do

“In the early-to-mid 1980s, I went to a class that taught vinyl repair using an iron. The man who taught the class could practically do an invisible repair, and it was strong! So I bought an iron that day and practiced and practiced and practiced until I became pretty good at iron repairs. I also learned so much about the value of good training.

“I took another class on what was called a hot-grain transfer repair. This is where you would heat up a silicone grain so hot that it would smoke (rather than heating up the substrate). Then you would lay the grain down on a repair after applying a new type of vinyl repair compound that would cure at low temperature, curing the compound and the substrate all together and leaving a nice grain.

“At that point, the only time I would use a heat gun was when I did a hot-grain transfer. The rest of the time I would use an iron, and I found that my repairs would last much longer.

“These new techniques improved my skill until I could do those Toyota door panels! With the iron you could concentrate the heat to a more defined area and it didn’t get as hot as with a heat gun. This would allow you to leave it on the repair longer, so that the heat would radiate all the way through the repair. It seemed like all my problems were solved.

“Then I ran into another problem. I developed a new customer, a car dealership that kept used cars on a paved lot which had no electricity. The closest electricity was at the main dealership, but there was no place to work on cars at the dealership. So the only place I could do the vinyl repairs was at the body shop, a half-mile away.

“Every time I had to do a vinyl repair, I’d have to drive it to the body shop. It was such an inconvenience that I almost quit the dealership, but they were willing to pay more than other dealerships for their repairs. With the help of a friend who brought me into this business, I started researching, trying to find something I could use that didn’t require electricity or cords of any kind.

“We found a product called the Ultratorch. It was a butane-powered heat gun without forced air, but that would radiate heat up to about 1,200 degrees. This worked on the smaller repairs, but for the larger ones I still had to drive to the body shop. So my friend suggested attaching an iron to the butane torch. Brilliant!

“We came up with a cordless iron that worked off a butane torch. This solved my problems and locked me into the dealership, because nobody else had this kind of portability.

“Just imagine, I could do vinyl repair anywhere and never have to run an extension cord. I decided to show my invention to a vinyl repair supplier, and they loved the idea. They did have one stipulation, in that I would have to teach a class on how to use this tool—and that’s how I started teaching vinyl repair.”

Heat Gun Vs Iron Or Both

“The supplier also wanted me to teach how to use the heat gun along with the iron. In the course of teaching these classes, I discovered that by using the heat gun first to start and cure the repair, and then finishing it with the iron, I could do a nearly perfect vinyl repair. This was a huge development in my skill level.

“I even use this process to this day on certain vinyls. However, things changed around 2000 when they came up with vinyls that cannot take the heat of even an iron. Today, we have materials that need to be cured at such a particular temperature that overheating them can ruin the material and make it hard to the touch. Under-curing the material will make it weak and the repair won’t last.

“There are now so many different types of vinyl and leather that it is critical to be as accurate with your temperature as possible. Nowadays, I mostly do new-car warranty repairs, show cars with exotic materials and warranty repair on RVs. In order for the repair to last, I need to use as close to an exact temperature as possible.

“One of the main tools I use is a thermostatically-controlled heat gun. It is accurate to within 10 degrees. Some of the vinyls (and leathers) today are so sensitive that a variance of just 20 degrees can ruin the material. There is also an iron that attaches to the heat gun, giving you the best of both worlds.

“In summary, the answer to the question about whether a heat gun or an iron is the best for vinyl repair is—both! Depending on the material, you might need either or both. Many techs can lay a better grain with an iron than with the heat gun.

“In other situations, it is best to repair the vinyl with the heat gun at low temperatures, coat it with a solvent vinyl coating, and then iron in the final grain at a hotter temperature. Above all, working to develop your skill through training and practice will allow you to answer this age-old question for yourself.”

As I finished the last sentence of the chapter, a three-foot-tall librarian came from behind a footstool and started whacking me with a rolled-up newspaper, chiding me for my spectacular entrance and the noise that resulted. As I realized that whoever had fired the shots was obviously a master of disguise (since no one else around seemed to hear the shots or see the shooter), I decided I better try to either wake up or find my medication.

The old-style “Snowshoe” iron in Doug Snow’s hand was made and used in the ’80s, and is no longer available. The photo on the right gives a clear view of the iron. The technician could adjust the temperature in order to use the iron on temperature-sensitive vinyl.